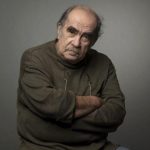

Bass player, band leader, producer, composer, record label owner, festival organizer… Among countless of achievements, Snarky Puppy’s Michael League has so many titles to be used before his name that it is almost impossible to introduce him with a few sentences without missing a thing. There is a great section on their site that explains everything in detail.

So here is direct quoting:

Michael League is a 3-time Grammy Award-winning musician based out of Brooklyn, New York. He is the creator and bandleader of instrumental music ensemble Snarky Puppy and world music group Bokanté, co-owner of Atlantic Sound Studios, and founder of the record label and music curation source GroundUP Music.

Michael attended the University of North Texas’ jazz studies program for 4 years, then moved to nearby Dallas for another 3 years, where he worked with some of the most influential figures in modern gospel, R&B, and soul music, and was mentored by legendary keyboardist Bernard Wright (Miles Davis, Chaka Khan) before moving to Brooklyn, New York, in 2009, where he currently resides. As an instrumentalist and producer, he has worked with a diverse range of artists in pop (David Crosby, Laura Mvula, Lalah Hathaway, Joe Walsh), gospel (Kirk Franklin, Walter Hawkins, Marvin Sapp, Israel Houghton), jazz (Terence Blanchard, Esperanza Spalding, Joshua Redman, Wayne Krantz, Chris Potter), and world music (Salif Keïta, Eliades Ochoa of the Buena Vista Social Club, Susana Baca, Carlos Malta, Väsen).

We had a long, nice chat with Michael and talked about the new album, today’s concert for Istanbul Jazz Festival and his times here in Istanbul before getting carried away with discussions of politics in the world and in the jazz scene.

Snarky Puppy will be at UNIQ Open Air today (July 9th) and for those who cannot wait any longer to see them live again after 4 years, or even better, for the first time ever, here is appetizers for you to start your day right.

- You’re a wanderer in music, inspired by so many cultures, genres. You travel around the world, study different music and instruments. How did it all start? Who influenced you through this journey?

I think my brother who is a musician, is probably the first person who started feeding me with music from around the world when I was in high school. I’m just curious, that is the main thing. When I hear a sound that’s new, I’m really curious about it. I want to learn about it and figure out how to somehow use a part of it on my own thing in a way that is respectful. It’s more a personality trait than anything else.

- I’ve read somewhere that your brother is also who introduced you to jazz. And afterwards, you went to college in Texas. But you always say that there’s more than what you were doing at school so at some point you dropped out. What can we say made you the Michael League we know? And more specifically, how did you find yourself playing with Erykah Badu in a church?

You’ve done a lot of homework there. (laughs)

I just dropped out of college; I was playing gigs pretty much every night. I was playing at bunch of white churches. A friend of mine called me to play at a jam session in Texas. So, I went to play and met this guy named Philip Lassiter who at the time was just a church band leader. But then he became the head of Prince’s horn section, a Grammy winning producer. At the jam session, Phil heard me play funky stuff and said “Do you play at churches?” and I said “Yeah” and he asked “Would you play at my church?” and I said “Yeah whatever, a gig’s a gig” you know? When I showed up to that church, I realized that the band that I was playing with was Roy Hargrove’s RH Factor. I didn’t realize it until we started playing, but then I recognized the saxophone tone and that snare drum sound and then I started putting it together. And through those guys I got to be a part of this very rich black music scene in Dallas. Erykah Badu’s band, Marcus Miller’s band, Roy Hargrove’s band you know. And I just stared playing with those musicians and that just became my community. I grabbed a bunch of the Snarky Puppy guys, told them about it and they became a part of the community as well. That was probably the most formative musical experience of my life because it was the moment in which I really felt like I developed a voice that was really mine, that was also very expressive and that I felt very comfortable being myself and not feeling like I was just trying to play like some old dead guy.

- You came back and forth to Turkey and you’ve studied with musicians like Tarık Aslan. We’ve seen you at jam sessions in Istanbul, at South Eastern parts of Turkey, later on going to the Middle East. What was it all about, what were you looking for and have you found it?

Tarık Aslan is my teacher. Whenever I was coming to Turkey, I was studying with him. I was in the South East, in Mardin, for his wedding. I also started studying dohola with Erdem Erol, who is one of the teachers at Mısırlı Ahmet School. I was there for 6 weeks at one point, went there for a few days or a week, at any chance I could to take lessons and study erbane with Tarık, and dohola with Erdem.

- I guess we were able to hear a bit of that in your latest albums with both Snarky Puppy and Bokanté? Say last song on the album, Immigrance?

I started writing it on oud and played it during the recording, so I guess there’s a little bit of feeling a lot of Turkish music has. I’m not Turkish, I’m not a Turkish musician so I don’t want to say it’s Turkish because it’s not my thing. But sure, I think there’s a lot of influence from my time there. Also, it makes a lot of sense because I was there when I was writing the song but it also has an Argentinian feel, like tango. And it’s interesting, there’s a lot of similarities between the two. There’s a lot of Turkish tango dancers actually, like world class. I think there’s a musical, cultural relationship there.

- You’ve been here with Snarky Puppy in 2015, how does it feel bringing the band back?

Great. I’ve spent a lot of time in Turkey over the last 4 years. To bring them to Istanbul again is very special because I’ve made a lot of friends there, I’ve studied music there. It’ll be cool to have the boys back in town.

- How do you manage to keep all those people in the same band? They’re so diverse culturally, mentally. And it’s been 15 years, right? The band grows even larger now, how do you do that?

First step is listening to people, not being a tyrant. I think respecting everybody and understanding not just that they have their own feelings and can get hurt but my band is not their dream and recognizing that. It’s my life, my dream but I have to understand that the people in my band have other desires, other dreams that they want to pursue so I try to create a system that allows that. Where they can be a member of the band and benefit from the association with the band but where they can have the option to say “No I don’t want to do that tour, I want to be on my own tour”, “No, I really want to make my own record and take a few months” etc. and they’re free to do that. The guys have started their own families now, so if a guy calls me and says, “I don’t want to be on tour for 10 months, I want to be with my daughter”, I’m like “okay, cool, no problem”. I think normally it wouldn’t be that way because you only have one drummer, one percussionist but in Snarky Puppy we have 3 drummers, 3 percussionists, 6 horn players so we can always adjust our existence for the individuals in the band. I think that keeps people close to the band. They’re just such great musicians and people that you enjoy being around them, on tour with them.

- How many of you are we going to see at the festival?

I think 10.

- What can we expect to hear at the concert, except for the new album?

We do a different setlist everyday but there’ll be songs that we always do. And also, we’re going to have special guests from Istanbul.

- What are your festival thoughts? Have you ever been in Istanbul Jazz Festival before?

Bokanté played at Istanbul Jazz Festival 2 years ago at Beykoz Kundura. And I really loved playing there with Bokanté. I got to know the administration well. I love the attitude of the festival, and that they kept doing it despite the terrorist attacks which happened like, I think a week ago or something. Guess the attacks were 4 years ago. I obviously love Turkey which is why I spent almost 2 months living there. But also, just the way that people appreciate music, I really like that a lot. When I was there, I was going out to see concerts and people really have a genuine love for music in Istanbul. So, playing for people like that is a really refreshing experience, it’s not always like that.

- Since you’ve been here plenty of times, there must be loads of crazy stories you have. What was the weirdest thing that happened to you here?

When we played at CRR (Cemal Reşit Rey Concert Hall) and I came back a couple of months later to spend a week studying with Tarık, it was supposed to be for 3 days. But then I was having such nice time that I kept moving my flight to the next day and the next day. I decided to stay another extra day and we were in def/erbane rehearsal in this Kurdish building just off the İstiklal on a very high floor. I heard gun shots in the street. And everybody was just super normal, and they were like “Well, yeah”. Apparently, it was supposed to be the Pride Parade but the government cancelled the parade for safety concerns but the gay community kept marching anyway. Every 20 minutes or so the police would come by and they would spray tear gas or shoot rubber bullets, and everybody would scream, run into buildings, then just go back out on the street and drink tea. And I was like “What is going on here, are you kidding me?”. It just kept happening. Then a cannister got into the staircase and smoked out the whole building. We were at the 5th floor, 25 of us had to run down the stairs and get out on the street just trying to leave the area. The street was blocked, and the cops didn’t let us because we were a large group. And Tarık said “Look, we’re musicians, we’ve drums. We’re just trying to leave”. They were like “You have to go the other way”, so we turned around and as soon as we went the way they wanted to, there was a bunch of police officers waiting for us and they started shooting at us. So everybody had their erbanes on their back, running in all these different directions. Eventually we got out of Taksim area, got in taxis and went to Karaköy and they were just like “You guys wanna have a beer?”. What do you mean like you get tear gas and shot by rubber bullets then you go have a beer? (laughs)

- How did you like the taste though?

It was delicious. I tasted it for three and a half weeks. Lots of lemons. And I was like, okay cool, Turkey, here we go.

I flew the next morning and when I landed, my phone was exploding with people talking about the attack at Atatürk Airport. I flew out an hour, two hours before the attack. It was very strange. A week ago, it was paradise, but the last two days were crazy. But it was deep and in a way, it was really beautiful. My friend Tuğçe was crying when we were having beers and she said “I’m sad that you had to see this, we work really hard to make you feel welcome here and things like this happen, people think about us the wrong way.” Hospitality in Turkey is really amazing. It made me think about a lot of things as a traveler, it was an interesting experience.

- I’ve heard that you’re working on a solo album. How’s that going so far and what can you tell us about it?

It’s very much in its infancy. I’m just starting to write songs. I have a million ideas that I’ve recorded but I’m just starting to form and actually complete the songs. Very early but I’m excited about it, I’ve never done that before so.

- Let’s talk about the new album of Snarky Puppy. For the promo videos of Immigrance, you guys have mentioned the people you work with and the band members’ immigrant background. Supposing this idea came from after Donald Trump and far-right extremism, could you tell us more about your perception on the issue? And what do you guys want to say with this album?

We recorded everything and mixed everything before we even had an album title. It wasn’t like we made the record with the idea. After we mixed everything and I was listening to it all, I noticed as an observation like “Wow this has Turkish influence, this one has Moroccan influence, this is coming from a hip-hop thing, this one’s a funk thing” and I had this moment where I thought about the fact that no music is really yours. Even for funk at a certain point, even it’s from my country, I had to learn about it. And there are plenty of Americans who don’t know anything about funk, just like there are plenty of Turkish people who don’t know about arabesk. Just because it’s from your country technically, doesn’t mean that you are an expert on it or whether you have the ability to play it. So, it made me think about the journey music takes across continents and generations and how interesting how all that is.

As musicians we are always tracking the migration of music and we are also a part of the migration of music. Some Turkish kid is going to listen to Snarky Puppy and make some weird kind of music based on that with his or her identity as a Turkish person and maybe that creates a scene and becomes a genre and 300 years from now on some Japanese kid will discover it, you know? Everything is like a path.

Probably that stuff came to my mind because of what has been going on in the world and specifically in the US and the demonization of immigrants. This kind of ridiculous idea of calling someone an immigrant and demonizing them especially for a president whose father is an immigrant is short sighted. We’ve been doing this interview series just to show that. We have a lot of fans who support Donald Trump or Marie Le Penn or Nigel Farage and those kind of populist leaders. I wanted to show them this is what an immigrant looks like.

We have a guy in our band named Bobby Sparks and his neighbor is a racist but loves Bobby. He always invites him over and complains about black people. Bobby’s like “Hey, I’m black” and he says, “You’re Bobby!”.

We think like this more often than I think we realize. We do the same thing with Republicans etc. It’s human being, rather than demonizing people I think it’s more important to engage with them, be peaceful and try to expose them to things they haven’t thought about. I would love to be exposed to what I haven’t thought about.

- Everyone gets a different idea when listening to instrumental music. How do you manage to show where you stand at socially or politically, or to spread a message through music?

Snarky Puppy is by nature not political. We don’t try to spread a political message. I think there’s a social message just like in Bokanté and that message is evident by simply watching the band. You have a bunch of people from bunch of different cultures, playing music together and highlighting each other’s differences rather than trying to get everyone to be one thing. We really enjoy each other’s individual personalities. The music is about the music. But you can’t separate music from the person who creates it or from the society that feeds and nurtures the desire to create music in that moment. While there isn’t a song specifically on the record that’s about immigration or populism, you can at least capture the emotion. The tunes, even for us have specific emotions.

In Snarky Puppy it’s not so direct, it’s open for interpretation but in Bokanté, it’s ultra-direct. Because Malika is singing with words that are very pointing and I like having the option to do either one.

- What do you think a musician’s duty of reflecting the times as Nina Simone said?

There’s a great interview with Tom Morello from Rage Against The Machine where he says all music is political and if the music that you’re making does not address whatever is politically relevant at that moment in time, you’re basically giving approval to the status-quo. If I’m not singing about what’s wrong, on a political issue, I’m saying everything is fine and that’s why I can sing or write a song called Baby Baby Baby. He says in that way Justin Bieber is political. By not confronting any of the issues that humanity is encountering in the moment, he says everything is fine.

Not sure I agree with that but there’s lot of truth I believe.

In a country like yours, you don’t really have the luxury to argue with that statement. In my country, the political issues are more hidden. They are massive but it’s not like you’re getting tear gas in the streets or elections are getting turned over and cancelled. Because it is not so evident, people in my country feel like “Oh I can just be not political”. They have the luxury to do that but not in Turkey.

There are few American musicians except for the pop that take that stand of being non-political. I find it, it’s more for the fans. If I post anything that’s even remotely political, people are like “Just shut up and play”.

- Do you see a decrease in your fan base when you share a social or political statement? Do you lose fans because of that?

One time I posted something about the Women’s March, I was like “Just wanted to say that everyone in this band supports all of you marching in Washington DC”. It was the day after Inauguration, and there were a lot of people who commented and said, “Keep your stupid opinions to yourself”, “Congratulations on losing half of your fan base” etc. Even the half of the US does not support Trump, and he has a 4% approval outside of the States. People just don’t see it.

So I don’t engage in conversations about that. In fact, I’ve become so unhappy with the state in social media that I quit all my accounts. I just use it as a press release, we just share what we do and don’t care about the comments. Instead of reading those comments and waste my time answering them I’d just be reading a book or practicing.

A must question. What do you think about what happened between Branford Marsalis, Kamasi Washington and Robert Glasper? What would you say about this never-ending discussion of what jazz is and what it is not?

A must question. What do you think about what happened between Branford Marsalis, Kamasi Washington and Robert Glasper? What would you say about this never-ending discussion of what jazz is and what it is not?

I’m going to start by saying that I have great admiration and respect for all musicians. And it’s unfortunate to see things like that turning to drama. I think it’s very important as musicians we support each other publicly. Even if we don’t and even if we’re not fans of each other, I think it’s important that we at least support each other. We all go through the same struggles, we’ve all have driven around the country in crappy vans, we’ve all played gigs for no money and no audience, we’ve all spent countless hours in practice rooms trying to build our artistry and it’s sad when you see that kind of stuff get torn down by each other.

But I also think it’s important as artists that we’re honest. I think artists by nature are opinionated, at least the ones that have unique voices. We had a long conversation about this in the Snarky Puppy Green Room about two weeks ago. First off, I don’t think about Snarky Puppy as a jazz band. I think in a certain kind of way we’re almost more in the tradition of jazz than some piano, bass and drum trios in a way because we take the products of our environment and this moment in time and society and combine our desire to use that to make music with a knowledge of the jazz tradition which I would say that every member of our band has with the exception of maybe two or three guys. They have at least spent years and years studying and playing it. In a way to me, that’s kind of more in the jazz tradition than it is to play covers of Charles Mingus tunes or Miles Davis tunes because the jazz tradition is innovation. It’s taking the things from this moment in time and expressing yourself through them. But in another way, what Snarky Puppy does to me is like pop music with a lot of improvisation and freedom. If someone told me “You’re not jazz”, I would be like “Yeah, you’re totally right”. If someone told me I had a limited jazz vocabulary… I mean… A musician is much more than anyone sees. I’ll go 9, maybe 19 gigs in a row in Snarky Puppy without taking a solo and maybe someone who sees those 19 gigs would say “Oh he doesn’t improvise”. It’s not that I don’t know how to improvize or I don’t because you didn’t see me improvize. But to make this statement about another artist…

I think what Branford was trying to say wasn’t inherently negative. I think he was trying to say that Kamasi and Robert are doing their thing. That’s not more or less important or valid than jazz. But it’s just another thing. But I think the way in which he said it kind of justifiably provoked a certain kind of reaction from Robert. And I don’t think Kamasi said anything right? I guarantee you he would’ve told you “No comment”.

There’s this thing about the jazz community; people give you their blessing in a way. Playing an instrument like the saxophone, that is like the most famous instrument jazz, I think it must be hard to hear someone who is such an icon of that instrument in that genre saying something about you that could be thought as negative. It’s like Dave Holland saying in an interview “Yeah Michael League, I don’t know, he doesn’t have a jazz vocabulary”. That would be hard to hear. But I also think that Branford was saying like “These are musicians who are making certain kind of music and they are reaching a different kind of audience.”

But I bet Kamasi Washington has opened people up to jazz saxophone and now people are buying Branford Marsalis and John Coltrane records. I don’t believe that anyone is right, or anyone is wrong. I would never presume to say what it is that someone else does. Discourse as musicians is better when we are supporting each other.

- Any pieces of advice for young musicians that admire you here in Turkey?

Young Turkish musicians immediately start with a big advantage of coming from a musically rich place. A place with a very long, ancient history of beautiful music and mixes of different cultures. With that advantage, there’s a responsibility there to really learn something about that tradition from where they come. And to develop it into a thing that is really unique and that’s really theirs. Often times, we travel to Europe or to the Middle East and meet musicians that play American music in the American way. But because they are not and they have not spent time in the culture that created that music, they don’t really necessarily have much of an advantage in terms of understanding. Ideally, in order to innovate something, you have to understand it. So basically, there’s a tremendous advantage being Turkish and growing in that culture. There are so many possibilities on how to innovate using that experience of growing up there, combined with the fact that the whole world’s recorded music is available to everyone that has internet connection. But no matter what country you are from, the same things apply: you have to practice hard and long, you have to have an open mind and you have to have technical proficiency on your instrument but also an emotional connection, the ability to communicate that emotion to audiences. And I think for the first time we’re seeing the emergence of the song in having an important factor in instrumental music. I think in vocal music, it has always been about the song. But in instrumental music at certain point it stopped being about the song and started being about the playing. And now I think people are feeling that it’s important again, and I think it’s beautiful. Learning how to compose and learning how to play a song in a way that it’s understood is a wonderful skill.

Young Turkish musicians immediately start with a big advantage of coming from a musically rich place. A place with a very long, ancient history of beautiful music and mixes of different cultures. With that advantage, there’s a responsibility there to really learn something about that tradition from where they come. And to develop it into a thing that is really unique and that’s really theirs. Often times, we travel to Europe or to the Middle East and meet musicians that play American music in the American way. But because they are not and they have not spent time in the culture that created that music, they don’t really necessarily have much of an advantage in terms of understanding. Ideally, in order to innovate something, you have to understand it. So basically, there’s a tremendous advantage being Turkish and growing in that culture. There are so many possibilities on how to innovate using that experience of growing up there, combined with the fact that the whole world’s recorded music is available to everyone that has internet connection. But no matter what country you are from, the same things apply: you have to practice hard and long, you have to have an open mind and you have to have technical proficiency on your instrument but also an emotional connection, the ability to communicate that emotion to audiences. And I think for the first time we’re seeing the emergence of the song in having an important factor in instrumental music. I think in vocal music, it has always been about the song. But in instrumental music at certain point it stopped being about the song and started being about the playing. And now I think people are feeling that it’s important again, and I think it’s beautiful. Learning how to compose and learning how to play a song in a way that it’s understood is a wonderful skill.

Bir noktadan sonra gözlerim erimeye başladıysa da çok keyifli ve içten olmuş. Elinize sağlık